An Inner Void

I’ve been building a case that the vast majority of Jews in the post-Holocaust world are spiritual orphans, having been raised with no awareness of Mussar or the lineage of teachers who have carried the tradition for the past 200 years. I’m not quite ready to move on from this topic because it’s not just something that I want you to know, but I also want you to look and see the implications this has for your own life.

As I have experienced the writings of the masters of Mussar, they don’t just mention a topic, they have a tendency to hammer on it over and over, and I have realized that they did this in an attempt to ensure that their words would not just be understood but would penetrate and have an impact. I’m following their example here.

Rabbi Elya Lopian (1876-1970) defined Mussar as “making the heart understand what the mind knows” and that can only happen with a deep and powerful, not superficial, encounter with an idea.

So let me reiterate that it is quite probable that the designation “spiritual orphan” applies to you, as it does to me, and if so, there are real implications.

Being a spiritual orphan means that you likely came to experience a void in your inner life. Had you been connected to your spiritual lineage, you would have come to know that you should make a priority of nurturing the soul that is your primary aspect of being, and you would have sought connection with the divine. You would have taken to heart that your primary marching orders as a human being are to be holy. But if you were not guided in those directions, it is likely that you experienced an inner spiritual void. Maybe you just had this feeling that something was missing in your life, or maybe you felt this as a deep spiritual loneliness. It all reflects that empty space, and as I learned in an early science class, nature abhors a vacuum.

That inner void might have sucked into it anything that promised satisfaction. People in our generation have jumped into social action, politics, the arts, exercise, cooking and all sorts of activities in a way that suggests that they have been looking for connection and fulfilment. Of course, the clearest example is to be found in the many Jews who took on the spiritual practices of other traditions, like mindfulness meditation which derives directly from Buddhist tradition.

But the same phenomenon can be seen in the allegiance people develop for sports teams. There is no proportionality between the extent of some people’s passion for sports and the reality that what is actually taking place is that a ball is being moved over a line, or into a hole, or across a net.

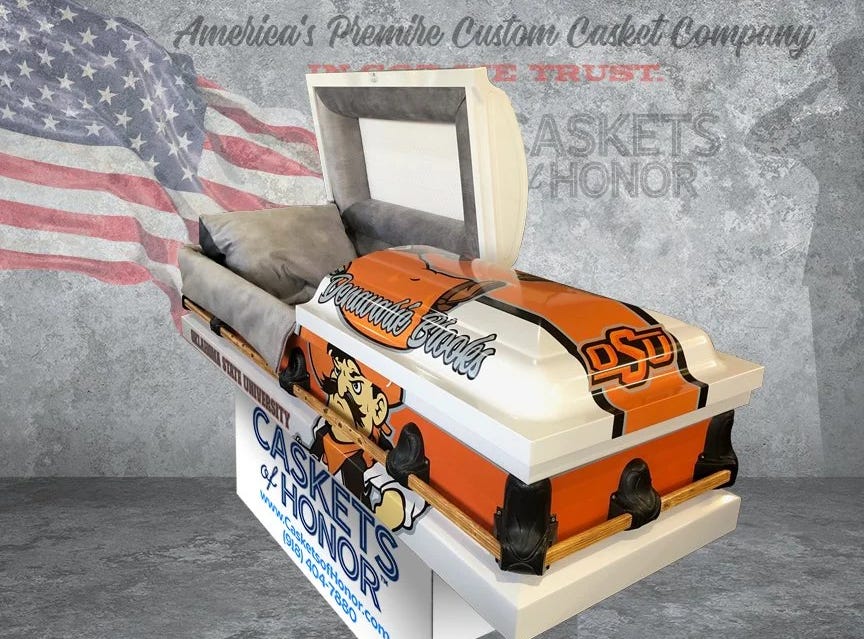

I was once talking with my late teacher, Rabbi Perr, tz”l, and he said to me, “Did you know that you can have your coffin painted in the colours of your favourite sports team?” I had never heard of such a thing and so I expressed my skepticism. “Check it out,” he said. And sure enough, the internet reveals that it’s now possible to go to your eternal rest wrapped in the colours of the Kansas City Chiefs or the Los Angeles Rams or whatever team has attracted your undying loyalty.

And, for people who might opt for cremation, you can have your ashes enshrined in cremation urn with New England Patriots – or other team of your choosing – ball decor and custom metal plaque. As Rabbi Perr said, “Check it out” at memorials4u.com.

Rabbi Perr would emphasize that there is nothing wrong with liking sports. When he rebuilt his yeshiva, he saw the value in having a basketball court installed. But there is a difference between enjoying sports and becoming a fanatic (which is, of course, the source of the word “fan.”). Sports is not the problem; making it into the most important thing in your life, for now and all eternity, is simply aiming too low for what a human being can and should endeavour to be.

The priority in the Reform Jewish world on tikkun olam seems to me to have a similar aspect. No doubt there are many social needs that we have an obligation to try to meet, but placing social action at the very centre of religious life seems to me to be a different sort of effort to fill the inner void that came to be when the Jewish world turned away from providing guidance for the inner life of the individual.

You probably have other examples of people who, in a sense, have worshipped something that is not spiritual but that you can see as an effort somehow to fill the spiritual-sized hole in their inner lives.

My examples so far have been the sorts of things that we see in the liberal Jewish world, but the same thing actually plays out in the world of Orthodox Jews, in a different way.

The word “frum” has come to be a near-synonym for “Orthodox.” “Frum” is a Yiddish word that derives from the German “fromm,” meaning pious or devout. The post-Holocaust Orthodox world has increasingly made a virtue of being frum and has characterized frumkeit in terms of ever greater levels of stringency in observance (i.e.,chumras, which are stringencies that people take on voluntarily) and conformity.

Look at a photo of a contemporary yeshiva community and the men will appear almost identical in terms of beard, black hat, dark suit and white shirt. Look at a comparable photo from pre-war Europe and you will see brown and grey hats of varying designs, striped suits in all shades, and more clean-shaven men than bearded ones.

This move toward ever more stringent observance and conformity was not generally supported by the Mussar teachers. Rabbi Aharon Kotler, who was a student of the Slabodka Mussar yeshiva and the founder of the Lakewood yeshiva in New Jersey (and the rebbe of my teacher, Rabbi Perr), would often say: “Frum iz a galech; ehrlich iz a Yid” which means that piety is a characteristic of a priest whereas the praiseworthy aspiration for a Jew is to be not pious but refined.

Rabbi Shlomo Wolbe, a very recent Mussar master, explains this drive to frumkeit. In his book, Alei Shur (vol. II, pp. 152-155) he explains that “frumkeit, as in all instinctive urges that occur in man, is inherently egoistic and self-centered. Therefore, frumkeit pushes a person to do only that which is good for himself.” Rav Wolbe went so far as to say that “frumkeit is just one letter away from krumkeit,” a Yiddish word that means “warped reasoning.”

In the terms of what I have been saying, taking on more and more aspects of being frum can be seen to be an attempt to fill the inner void of a spiritual orphan, not with spirituality but with meticulous and stringent religious performance.

And now, since we are at the time when the calendar tells us to look inward and take stock, let’s turn the spotlight around to focus on you.

Can you identify activities or allegiances you have developed which you can see might be understood as an attempt to fill that inner spirituality-shaped hole that came to exist in you because you were raised a spiritual orphan? Might that explain your passion for sports, or social action, or religiosity, or ….?

Have a good look and see what you can see and, if you would, please share your thoughts in the Comments section of this blog. I’ll be grateful to learn from your experience and insight.

** I am indebted to Rabbi Micha Berger for his translations of Rabbi Wolbe’s writing on frumkeit at https://aspaqlaria.aishdas.org/2022/09/28/rav-shlomo-wolbe-frumkeit/

A lot of food for thought .

There definately , in my opinion ,is a hunger for spiritual fulfillment in today’s times and I for one ,a person who is shomrei Shabat, together with my husband and incredible children and grandchildren, feel that void . Most times it is filled through family love and the closeness and joy we all share and the gratitude I feel for being a savta to such precious souls . I have been privileged to live in Israel for the last 40 years , having made alliyah from South Africa many moons ago and watch our children and grandchildren grow up as Israelis.

I also live in Kfar Adumim which is a mixed community of “ religious” and “ non religious” people living together by choice with tolerance and acceptance of other . This in itself, in my mind,means that we live in a healthy community with strong friendships of all kinds on a deeper level.

However , I do feel that more and more, probably since Covid and definitely since October 7 th that this void is growing and has become almost like a spiritual hunger which is not filled despite the comfort food I have been over indulging in and the shows I sometimes binge on ,with Netflix as well as other physical pleasures, to no avail. Of course there is nothing wrong with physical pleasures, on the contrary, but these do not in themselves fill the vacuum inside.

Yes,there is an inner soul felt lack and a huge distance from the head to the heart in many areas of my life and even if I know what it is, it’s not easily attained.

Is the reason based on your insights , possibly .

I did come from a traditional home with grandparents who left Russia before the First World War and filled my Jewish soul with both delicious Shabat meals and inner food for the soul .

So maybe I am not the one to comment but I definately agree with your premise that we are hungry and craving inner spiritual fulfillment.

Thank you for sharing .

Wow! Beautiful.